Stating the revealed preferences of choice.

Context

I am developing an article on the foundations of revealed preference (RP) and stated preference (SP) methods. This article is motivated by the common assumption in choice analysis that RP acts as a “Gold Standard” and SP is an ersatz option used only as a last resort when RP data are unavailable. From the outset, I recognize that the article may face challenges to publication. A non-exhaustive list of reasons would include positivist epistemology bias (“where is the data?”), gate keeping (“you were not invited to submit an editorial article”), and ontological bias (“but this is the way the world works”). I am a bit sardonic but also pragmatic. I will post the full article online for posterity and my graduate students to review while it is under review for publication.

Harvey (1969) and Gregory (1978) argue that if we start from different epistemologies, we will get different results. This is as good a starting point as any to situate this post. Epistemology concerns how we know things and the methods of validation our knowledge. RP theory is premised on observation of choice providing knowledge of “choice”. This is a good start point for a choice analysis, but does RP represent preferences? It depends on a number of factors, which we can consider through the lens of ontology, or our theory of the nature of reality. RP assumes a world in which individuals are free, unconstrained agents that make free and informed choices. Simon extended the rational choice framework to “bounded rationality”, in which individuals are free to make decisions but possess only imperfect information. Sheppard and Barnes state that “[t]heory and observation cannot be separated from one another, and the ontological priority of the one or the other is an interminable dispute in philosophy”.

A Natural Analogy

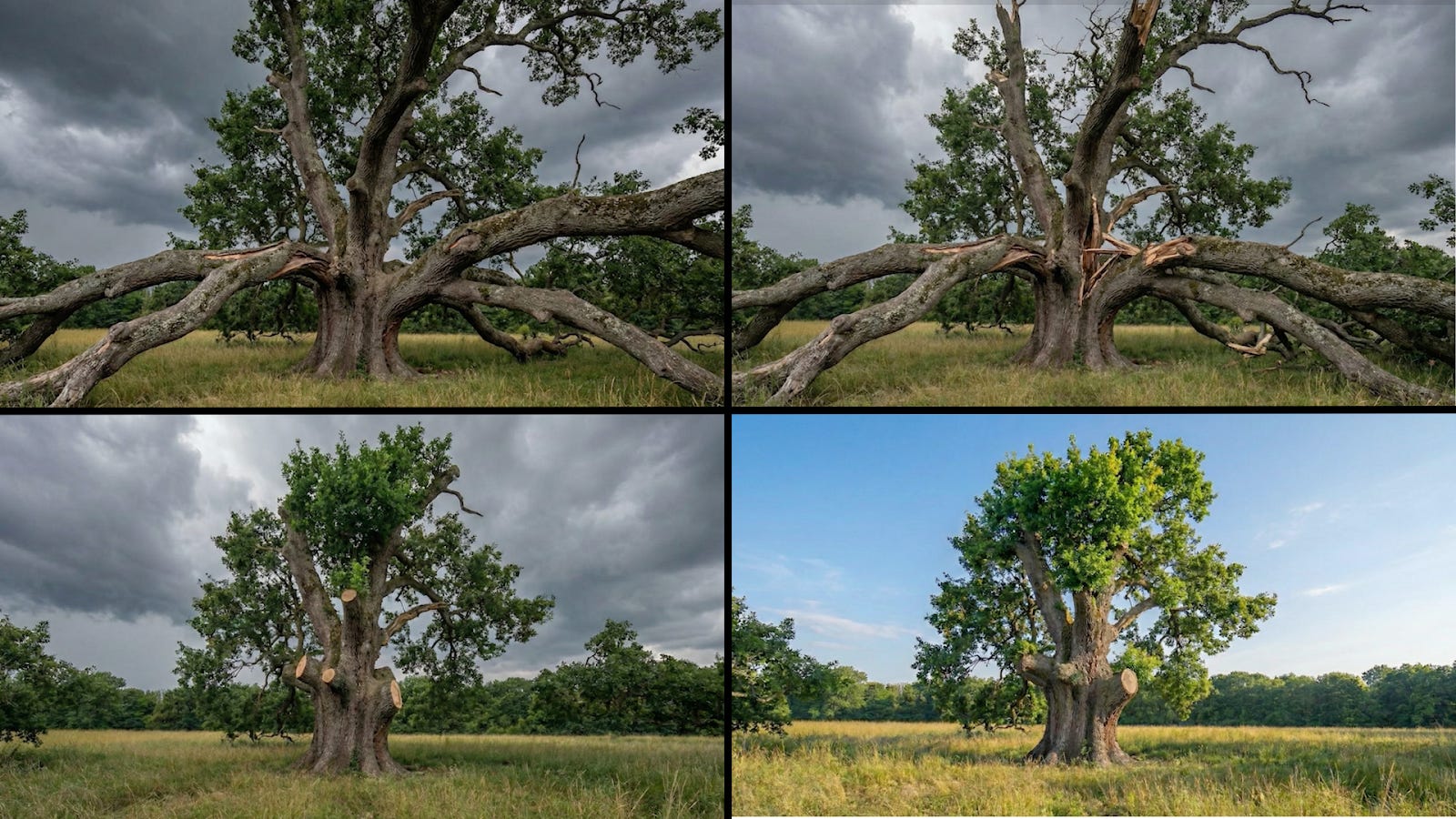

I was struck by an analogy given by Nate Hagens on a recent episode of The Great Simplification podcast. Hagens was discussing sunk costs - a past expenditure of time, money, effort that cannot be recovered - which raised the thought for me that observed RP data is a sunk cost. These costs include the identity, status, and institutional structures encapsulated in our past choices. Hagens makes a nice analogy to an oak tree, which was badly pruned many decades ago. The tree grows out in an unbalanced way, with heavy limbs at odd angles. “Those branches of the tree are sunk costs in wood.” When a storm comes, the tree will be torn apart. A good arborist will study the structure of the tree, making careful cuts that “guide the new growth in stronger directions”. The tree may be smaller, but it have a healthier and more resilient structure.

Hagens is talking about the size and diversity of the economy and our patterns of consumption, but I believe we can also interpret his argument in terms of the RP-SP dialectic. Positivist research is based on an existing reality at a fixed point in time (or over a fixed period). RP theory follows Aristotelian logic: a hypothesis either true or false and stays that way. Positivist science works because it empirically tests hypotheses on the current system, therefore accurately describes existing structures. Dialetical materialism says that we must also consider the historical roots, to continue the nature analogy, that led to the current system of consumption and available options.

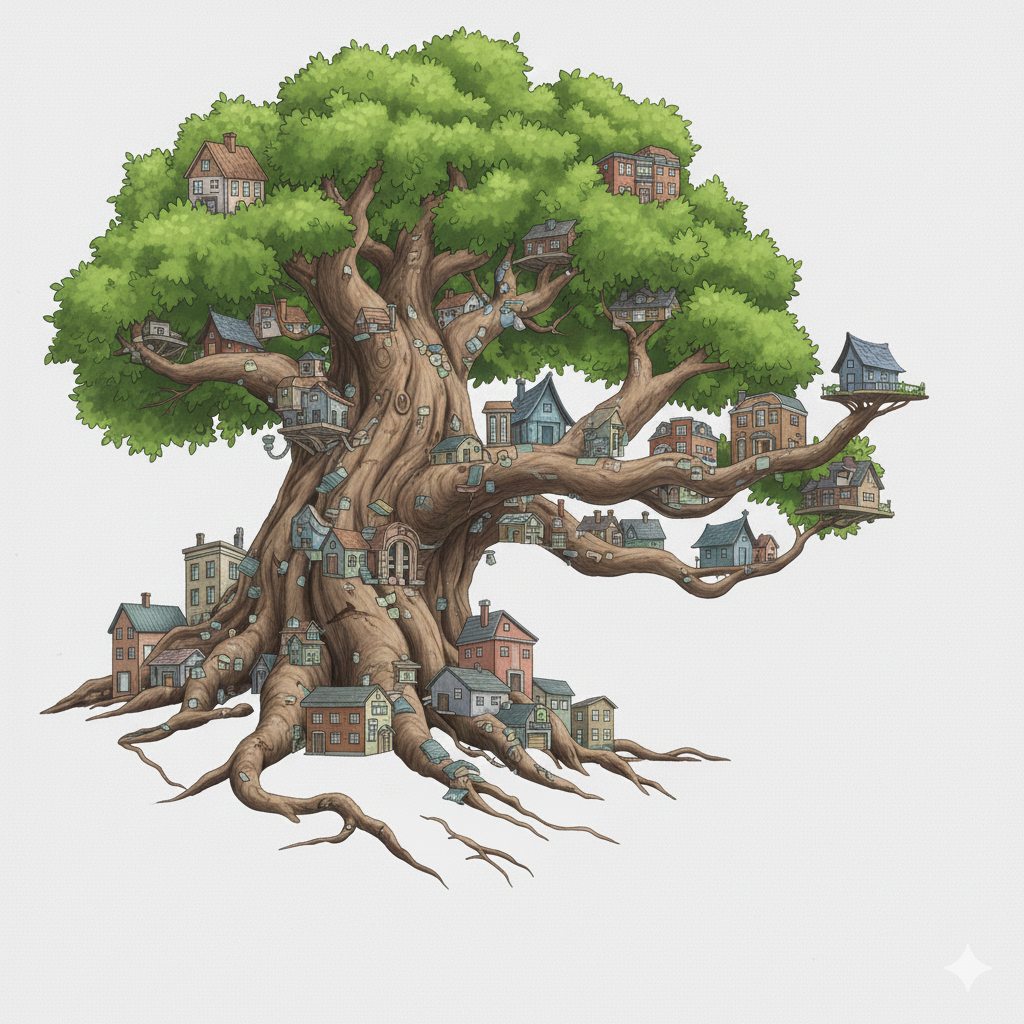

I’ll bring things closer to home with a dwelling location choice example that builds off the analogy of Hagens from above. In many North American cities, the available dwelling options are some combination of detached houses of various sizes and colours. The neighbourhood is a mix of houses, small parks, and perhaps a gas station on the main road. RP theory would suggest that this pattern is the revealed preference of households. For a wide variety of reasons, this is a highly biased and (I would argue) problematic framing. The left-hand tree represents my attempt to map Hagens’ analogy onto the problem. The tree is dominated by detached houses, imbalanced, and unhealthy. The right-hand tree includes a more diverse mix of housing options and is much healthier. Of course, I am making a highly normative decision by making my preferred neighbourhood a healthy tree, but it is my prerogative as the blog author. The point I seek to make here is not that we should all live in high-rise apartments. Rather, we must provide households diverse options that recognized their diverse neighbourhood and dwelling preferences. This is an SP question - what do people say they prefer in their neighbourhoods?

Conclusions

There is obviously much more to say on this topic. In the full article, I will provide the mathematical and theoretical details of RP, as formulated by Samuelson and McFadden from different perspectives; I would say Samuelson’s RP theory is more theoretical and mathematical while McFadden’s theory aligns with his more pragmatic econometric approach to economics. I am also using crude and unnuanced interpretations of RP and SP in this post. I will provide more nuanced interpretations and groundings in the literature in the full article. The main point to make in this post is that RP is not a “Gold Standard”. It has its merits but must be considered in its historical context. Our decisions as consumers are heavily influenced by the alternatives made available to us, budget and information constraints, and socio-political forces. In the same way, SP is not a perfect solution. Respondents can say what they like in a survey. Both RP and SP are necessary tools to formulate policy and plan for the future but neither is sufficient.